Early Taoism is known to us through two famous works, the Chuang-tzu and the Lao-tzu or Tao Te Ching, both of uncertain date but originating probably in the fourth or third century B.C.E. The Chuang-tzu, in thirty-three sections, is made up of writings attributed to the philosopher Chuang Chou (flourished fourth century). The Tao Te Ching, in two parts and eighty-one short sections, has traditionally been attributed to a figure known as Lao-tzu , or the “Old Master.” The earliest biographical account of Lao-tzu is that found in chapter 63 of the Shih chi, or Records of the Historian, a voluminous work on Chinese history written around 100 B.C.E. by Ssu-ma Ch’ien. According to that brief notice, Lao-tzu’s surname was Li, his personal names were Erh and Tan, and he was a native of Ch’u, a large state situated in the lower Yangtze valley. He served as historian in charge of the archives of the Chou court, which means he must have resided at the Chou capital in Lo-yang . The account gives no dates for his lifetime but states that when Confucius one time visited the Chou capital, he questioned Lao-tzu concerning matters of ritual. From this it has been assumed that Lao- tzu was a contemporary of Confucius. After describing the meeting between the two philosophers, the biography goes on to say that Lao-tzu, “viewing the decline of the Chou royal house, eventually quit the capital and journeyed to the Pass,” presumably the Han-ku Pass, far west of Lo-yang. There the Keeper of the Pass, surmising that the old man was about to withdraw from the world, asked if he would write a book for him before doing so. “Lao-tzu thereupon wrote a work in two parts, expounding the meaning of tao and te in some five thousand characters, and then departed.” “What became of him afterward,” the historian adds, “no one knows.”[1]

[1] From the Introduction to the Tao Te Ching Lao-Tzu by Burton Watson (Shambhala, 1993) xxv.

Lao-Tzu | 5th or 6th Century BC, China

Chuang-Tzu / Zhuangzi | c.369-286 BC | Pronounced – “ju-ung-za” 莊周夢蝶

Chuang-tzu was a native of a place called Meng (probably in present-day Henan, south of the Yellow River), and he once served as “an official in the lacquer garden” there…. at the same time as King Hui (370-319 BCE) of Liang and King Xuan (319-301 BCE) of Qi.

Chuang-Tzu is best known for his stories, parables, his use of irony and paradox, and his humour.

“One night, Zhuangzi dreamed that he was a carefree butterfly, flying happily. After he woke up, he wondered how he could determine whether he was Zhuangzi who had just finished dreaming he was a butterfly, or a butterfly who had just started dreaming he was Zhuangzi.”

From Victor H. Mair’s introduction to Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu (1998 edition):

“The Tao Te Ching is extremely terse and open to many different interpretations. The Chuang Tzu on the other hand, is more definitive and comprehensive as a repository of early Taoist thought. The Tao Te Ching was addressed to the sage-king; it is basically a handbook for rulers. The Chuang Tzu, in contrast, is the earliest surviving Chinese text to present a philosophy for the individual. The authors of the Tao Te Ching were interested in establishing some sort of Taoist rule, while the authors of the Chuang Tzu opted out of society, or at least out of power relationships within society. Master Chuang obviously wanted no part of the machinery of government. He compared the state bureaucrat to a splendid ox being led to sacrifice, while he preferred to think of himself as an unconstrained piglet playing in the mud.”

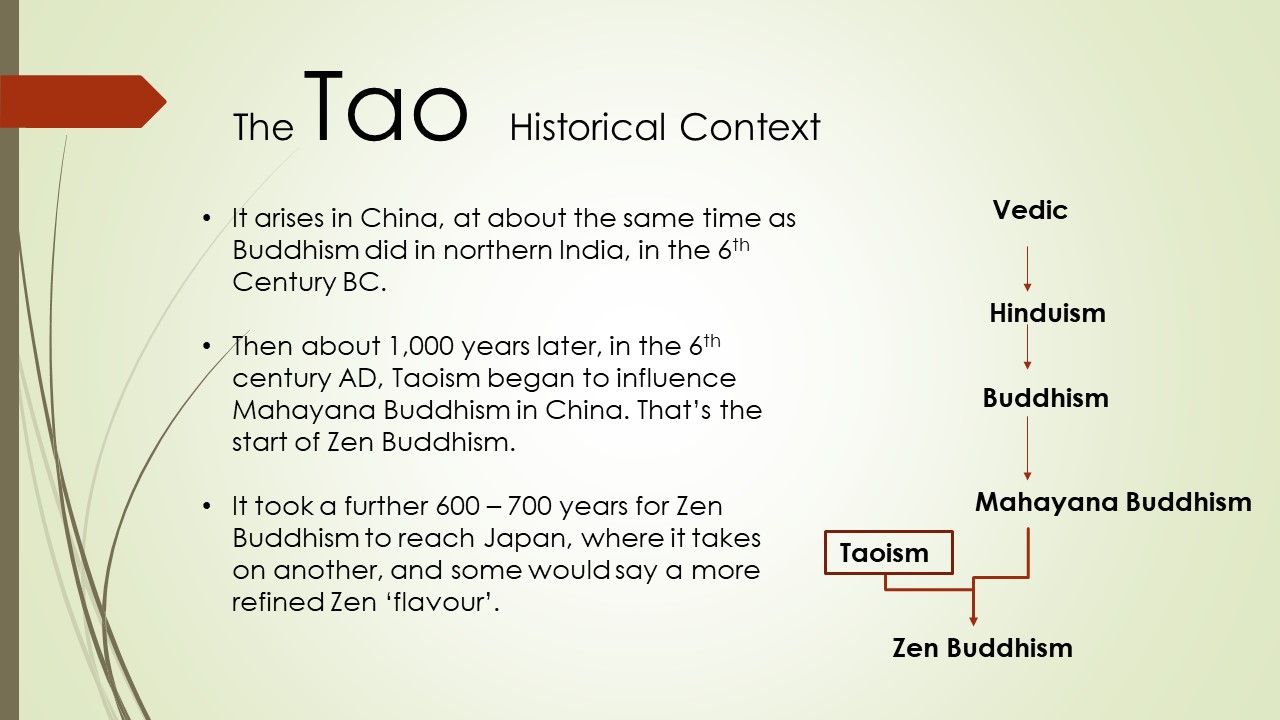

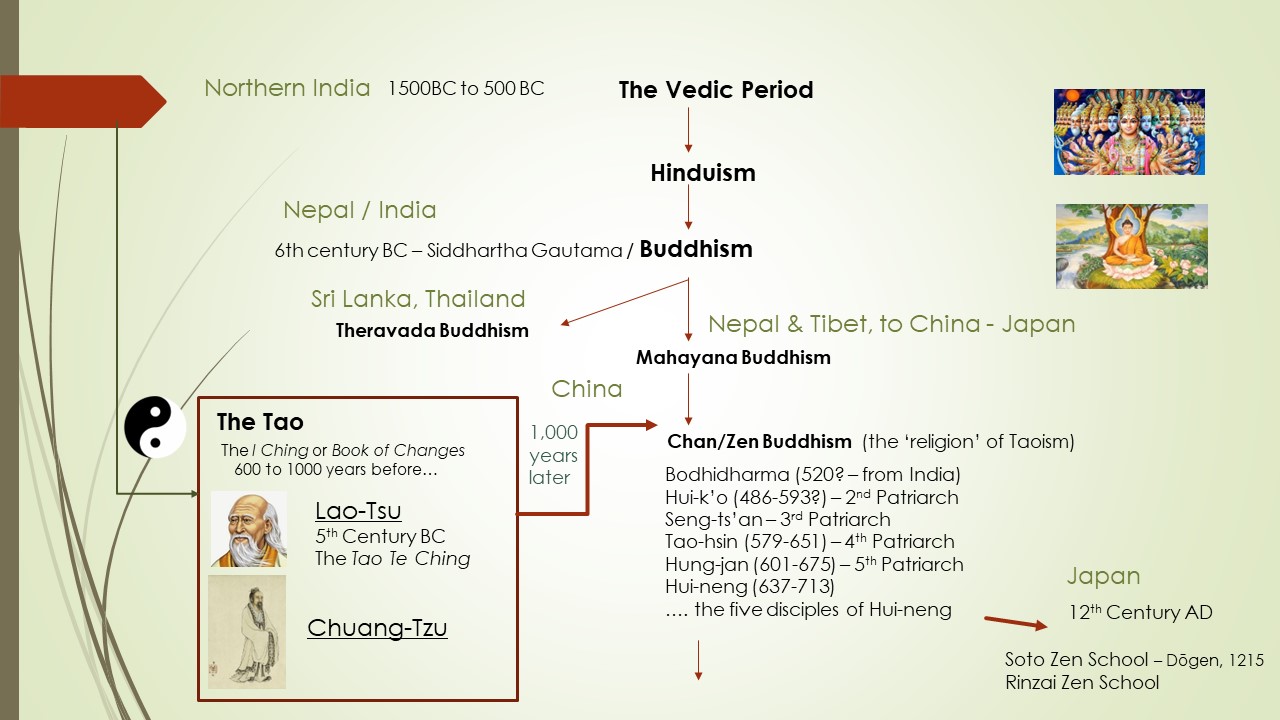

Historical context